Guest Blog: NatureLink and the Circular Economy by Alex Chapman, Gaia Resources

I had the good fortune to attend two very interesting events recently. And if I learnt anything from these two rather different focus groups it’s that there is a real momentum across business and the community to work smarter to address the serious environmental issues we are facing.

The key reference binding these two events was the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals at the core of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

NatureLink Perth is a relatively new initiative hosted by Murdoch University that aims to provide a hub for collaboration between diverse stakeholders to integrate nature into our city, sustain our world-class biodiversity, and provide a healthy, liveable city that benefits the economy, environment and its people.

The NatureLink Perth Symposium 2019 was held on the 4 July in the Kim Beazley Lecture Theatre at Murdoch University. The Symposium provided collaborative space to discuss efforts to enable nature-sensitive urban design and nurture a biodiverse, liveable city. It was attended by a diverse set of stakeholders, with some 202 registered participants including 83 organisations, and provided many opportunities for networking and input on the key goals and challenges.

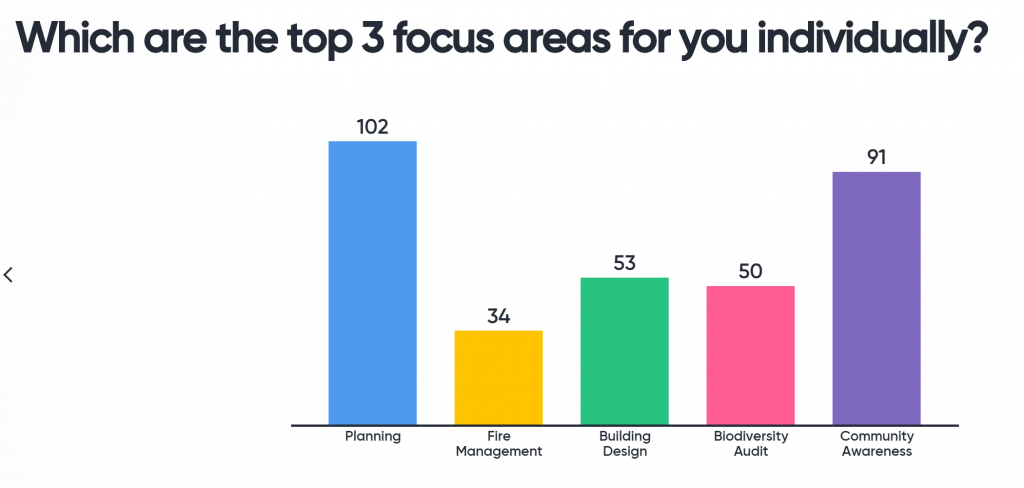

Direct engagement and input from attendees using an interactive presentation platform was an excellent and efficient method for immediately capturing audience responses and feedback for later reference and sharing. Five key issues were presented and formed the basis of the panel discussions at the core of the day (each with a lead panelist).

Planning: How can State and Local Governments work together to better integrate biodiversity and green-space into planning at all levels? (Renata Zelinova, WALGA)

Fire Management: What are the conflicting elements of bushfire management and biodiversity conservation? How can we balance them to benefit both? (Tim McNaught, DFES)

Community Awareness: What facilities, education and community engagement programs should we target to better connect people with nature and sustain biodiversity? (Carmen Lawrence, CCWA/UWA)

Design Implementation: What are the challenges in getting approval for nature sensitive urban design and how can we improve design regulations to mainstream it? (Chris Green, UDIA)

Biodiversity Audit: What are the critical information gaps in biodiversity info and how can we obtain the information needed and collect it innovatively? (Richard Hobbs, UWA)

After the extended discussion session, where some quite passionate statements from both panellists and audience about clearing for development, loss of species, habitat and expertise, and the need to integrate and liberate knowledge, attendees were asked to indicate what they considered their top three priorities. The resulting graph, from 118 individuals, is shown below – improving planning and building regulation were considered key priorities, as was increased community awareness, engagement and advocacy.

In the afternoon session we heard from a number of the brilliant young NatureLink interns, most about to complete their studies, as well as local case studies on nature projects – Cockburn Community Wildlife Corridor (Sue Marsh), Saving Urban Turtles (Anthony Santoro, Murdoch U.), and Piney Lakes design trends (Kelly Fowler, City of Melville). The final keynote by Tom Hatton (EPA) was an inspiring call to listen to and work with the next generation, for the future. The take-home message to me was that local actions are the only real way to achieve global outcomes.

The immediate outcome of the symposium for the NatureLink team was to how to move into their collaborative phase using the information provided at the symposium. A precis of these considerations by this smaller workshop was distributed.

The following day I attended a morning session on The Circular Economy, organised by the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre (AMGC) and hosted by the WA Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCIWA).

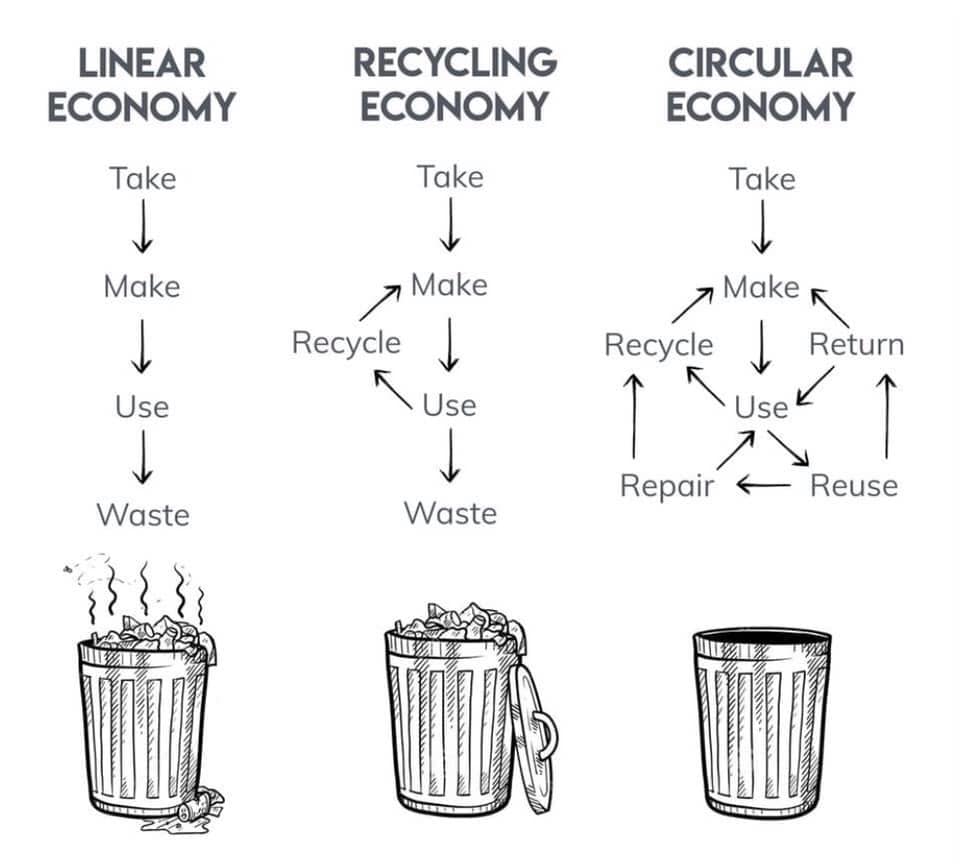

The ‘Circular Economy’ is a strategy for changing the way to produce, assemble, sell and use products to minimise waste and to reduce environmental impact, while being advantageous to business by maximising the use of valuable resources and contributing to innovation, growth and job creation.

The graphic at right simply illustrates the key difference between a linear and circular economy. The keynote speaker proposed that to the ‘4 Rs’ of Return, Reuse, Repair and Recycle can be added a fifth – Re-form.

The keynote speaker was Professor Veena Sahajwalla, Director of the UNSW SMaRT Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology. Veena and her team are working closely with industry partners to deliver the new science, processes and technologies that will drive the redirection of many of the world’s most challenging waste streams away from landfills and back into production; simultaneously reducing costs to alleviating pressures on the environment.

She is reimagining the global supply chain by demonstrating the viability of ‘mining’ our overburdened landfills to harness the wealth of useful elements like carbon, hydrogen and materials like silica, titania and metals embedded in our waste. One of the key elements to this vision is the implementation of smart micro-factories that can operate on a site as small as 50 square metres and can be located wherever waste may be stockpiled.

To round out this line of thought about “thinking global, acting local”, I happened to read an article the following day entitled Geoengineer the Planet? More Scientists Now Say It Must Be an Option. While it looked at a range of planetary-scale technologies for ameliorating global warming, it ended with a very local solution, which made me reflect on the way nature and human technology can co-exist in the future world. Here’s one quote from the article to finish.

In fact, natural regrowth is usually better than planting, since “allowing nature to choose which species predominate during natural regeneration allows for local adaptation and higher functional diversity,” says Robin Chazdon, an ecologist at the University of Connecticut. A study published in March by 87 researchers, including Chazdon, concluded that “secondary forests recover remarkably fast” with 80 percent of their species typically back in 20 years and 100 percent in 50 years.

It looks like it could be a win-win, delivering a climate payoff on the scale of geoengineering without any of the downsides. Tim Lenton of Exeter University, a proponent of research into geoengineering, says it could be an ideal solution. “I am against introducing new forcings such as sulphate aerosol injection in the stratosphere,” he says. “But I am in favor of emulating and enhancing natural feedback loops and cycles, such as regenerating degraded forests.”

It would, he says, strengthen the biosphere’s natural forces of self-regulation that British scientist James Lovelock has termed Gaia. Lenton has a new term for what is required. Not geoengineering, but Gaia-engineering.

If you’d like to talk about how our Gaia-software-engineering can help with your environmental projects or about any of the ideas presented here, then leave a comment below, start a chat with me via Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn, or email me directly via alex.chapman@gaiaresources.com.au.